As most people of a certain age remember, a cultural revolution took place in the streets of Birmingham, Alabama, in the 1960s. It was the battlefield of America’s Civil Rights Movement, a struggle for simple decency and common sense.

The story of Birmingham’s role in the long march to civil rights has been told and retold around the world. With the opening of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in 1993, the city found a place to tell its own story.

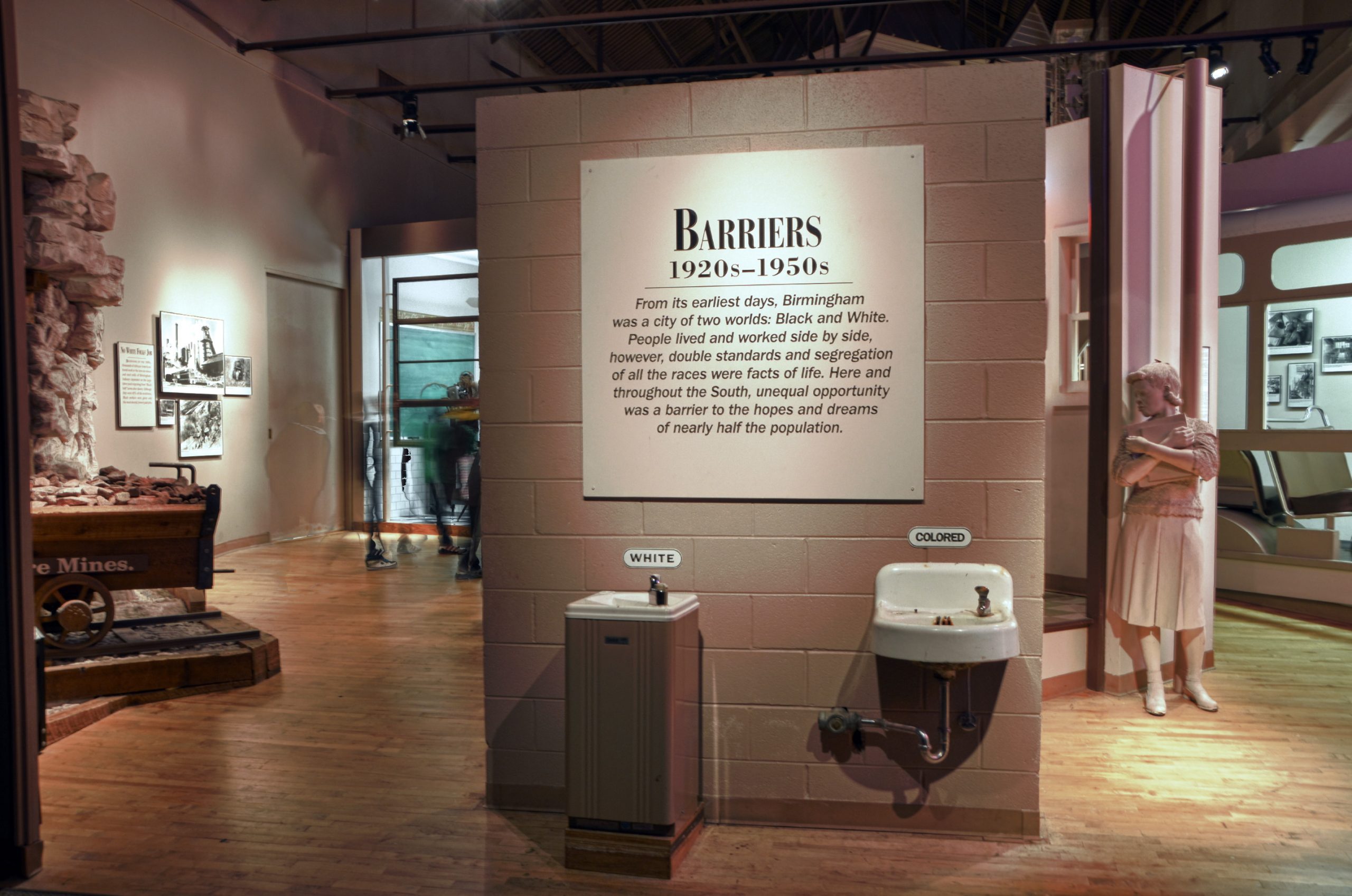

Though the events of the 1960s steal the spotlight, the Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham and Alabama evolved from a complex history of race relations in the American South. Richly detailed exhibits in the Institute reveal slices of Black and white life from the late 1800s to the present. A series of galleries tells the stories of daily life for African Americans in Alabama and the nation and how it differed dramatically from the lives white people of that era took for granted.

The Institute documents the rise of the movement and the succession of events it bore around the nation: the 1955 arrest of Rosa Parks on a Montgomery bus for her refusal to give up her seat to a white man; the U.S. Supreme Court’s bus desegregation ruling in 1956; James Meredith’s 1962 admission to the University of Mississippi.

The Institute documents the rise of the movement and the succession of events it bore around the nation: the 1955 arrest of Rosa Parks on a Montgomery bus for her refusal to give up her seat to a white man; the U.S. Supreme Court’s bus desegregation ruling in 1956; James Meredith’s 1962 admission to the University of Mississippi.

Just across the street is Birmingham’s most famous civil rights landmark, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Though Sixteenth Street Baptist was the church that drew worldwide attention, it was Birmingham’s Bethel Baptist Church that is credited with shaping the Civil Rights Movement here. Civil rights legend, the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, was pastor of Bethel Baptist Church from 1953 until1961. The church often served as a gathering place for discussions of civil rights among Blacks, gatherings that angered white supremacists. In 1958, Bethel Baptist was bombed though the church was empty at the time.

The bombing cemented Shuttlesworth’s fiery determination to bring Birmingham to the center of the Civil Rights Movement. His high profile in the movement incited other acts of violence against him. On Christmas night in 1956, a bomb was planted under the parsonage where he and his family lived. The blast destroyed the house, blowing up the bed Shuttlesworth occupied. Miraculously, he walked away from the destroyed parsonage unharmed.

Shuttlesworth later endured vicious beatings while trying to integrate schools, buses, and businesses. He remained active in the Birmingham struggle even after he moved to Cincinnati in 1961. A statue of Shuttlesworth at the entrance of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute pays tribute to, some say, an unsung hero and his self-described “agitation for civil rights.”

Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, across from the Civil Rights Institute is designated a National Historic Landmark. In the basement of the church on a September Sunday morning in 1963, four African American schoolgirls were changing into their choir robes. A bomb set by Ku Klux Klansmen ripped through that side of the church, killing 11-year-old Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley and Addie Mae Collins, all 14 years old. The bombing shocked and sickened the city and the world and was a turning point in the status of race relations in this country. (The story of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing is told with intensity in filmmaker Spike Lee’s documentary Four Little Girls.)

Adjacent to the Civil Rights Institute, Kelly Ingram Park served as a congregating area for demonstrations in the early 1960s, including the ones in which police dogs and fire hoses were turned on marchers by Birmingham police. Images of those attacks haunted Birmingham in the decades that followed, but they were the same images that were instrumental in overturning legal segregation.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Dramatic sculpture all around the park vividly depicts the events that took place there in the 1960s. Among the sculptures are three ministers kneeling in prayer, a tribute to the important role of Black clergy during the movement. The statue is based on a picture of the late Reverends John T. Porter, A.D. King, and Nelson H. Smith.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Also in the neighborhood is the A.G. Gaston Motel, where the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., regularly stayed in Room 30, meeting there with other civil rights activists to plan the scope of the Birmingham campaign. Motel owner and Black business magnate A.G. Gaston offered rooms at discounted rates to leaders of the movement. In 1963, a bomb was detonated below Room 30 causing extensive damage.

The nearby Fourth Avenue Business District remains active with restaurants, barbershops, and bakeries. This cluster of Black-owned businesses was the core of African American social and commercial life in the early 1900s and later when white-owned shops and stores refused to serve Black customers. Minority-owned businesses still operate in the district today, serving a steady stream of customers of all races.

The nearby Fourth Avenue Business District remains active with restaurants, barbershops, and bakeries. This cluster of Black-owned businesses was the core of African American social and commercial life in the early 1900s and later when white-owned shops and stores refused to serve Black customers. Minority-owned businesses still operate in the district today, serving a steady stream of customers of all races.

These sites together were named a National Monument as one of the final acts by President Barack Obama. In 2023, Birmingham is recognizing a 60-year anniversary of the momentous events that took place in the city in 1963.